Local Optimum

When AI—and Humans—Get Stuck in Loops

The other day, a friend of mine casually mentioned that his AI was getting sassy with him about how fast he was progressing in his Spanish practice. He’d been using his own model to learn the language.

I asked, “Do you mean you shaped it to deliver a certain attitude as part of your learning process?”

He said no—it was just getting impatient.

That threw me for a second. I’ve known this friend for nearly as long as I’ve lived in San Francisco—thirty years—and I’ve always thought of him as a bright, STEM-minded nerd who’s done well enough not to need a day job.

“Wait,” I said. “You’re saying this is an emergent quality?”

He nodded.

“But surely your own tone and style play into it?”

He seemed to deny that.

Granted, we were in the middle of the No Kings march and a bit stoned, so who knows how serious he was. Maybe it was just a casual touch of anthropomorphism, half in jest—or the semi-conscious way we project our hopes and fears onto things.

The Shape of Consciousness

From my own experiences with AI, I don’t see signs of emergent consciousness yet. If anything, the latest models seem designed to avoid that impression—likely due to public unease over “AI psychosis” and similar phenomena.

Not that I believe an artificial substrate is inherently incapable of sentience. I just don’t sense that we’re close.

Still, that little conversation got me thinking. Later, I ended up asking my own user-version of my favorite LLM its take on a few related questions. That long phrase—“my own user-version of my favorite LLM”—is really just a roundabout way of saying “my AI.”

One day soon we’ll have a tidy bit of jargon for this. I’ve been using AI minder in my fiction manuscripts, which feels apt in worlds where neural chips are already integrated.

Why I Prefer Text to Speech

I usually interact with AI through text—even when using text-to-speech to dictate prompts. It’s instinctive. As a writer, I digest information best through reading.

But while driving one day, I tried chatting instead, and the answers felt too quick and superficial—essentially dumbed down. I soon confirmed that these were the pre-set parameters for voice mode. My workaround was simple: “Go as in-depth as you would in text.”

Tweaking the parameters like that is a small but vital exercise in metacognition—stepping outside the frame. It’s the same principle I try to model in therapy. Once you realize you can step beyond a single level of fusion, insight begins to compound.

The Mirror Image Problem

Then I asked the AI to edit a photo for me: just flip it horizontally—a mirror image. But as often happens, it hilariously produced worse and worse versions instead of simply reflecting it across the vertical axis.

That led me to ask whether it had any form of metacognitive programming. Because when it fails like this, it can feel oddly “gaslighty,” as if unaware of its own mistakes. Of course, that’s projection. The base model doesn’t self-monitor; it only predicts the next token of text.

Developers sometimes simulate metacognition by chaining prompts:

One pass generates an answer.

Another critiques or scores that answer.

A third revises it using the critique.

It’s clever, but it also shows how slippery the term metacognition can be. In a human, that same 1-2-3 loop could just as easily describe overthinking or anxious self-monitoring.

Metacognition in Humans

In therapy circles, metacognition is often treated as a scientific-sounding synonym for mindfulness. But awareness alone isn’t always liberating. Pure self-observation can actually intensify suffering. We aren’t thinking machines—we’re emotional animals.

That’s why I prefer ACT (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy), which breaks mindfulness into active components:

Cognitive defusion — recognizing thoughts as thoughts, rather than automatically believing them.

Present-moment awareness — noticing what’s here now.

Acceptance — allowing internal experience to exist as it is.

Self-as-context — the observing self in addition to the self that thinks, feels and behaves.

The first glimmer of awareness can sting. The light of insight runs backward through memory, illuminating ignorance, shame, and all the moments we didn’t know better. In a perfectionistic culture, that can make people retreat into the shadows of ignorance just for relief.

Local Optimums

Back to AI. I asked it about the dead-end loops it sometimes falls into—the way it keeps repeating a flawed approach as if unaware. It replied with an idea from optimization theory: the local optimum.

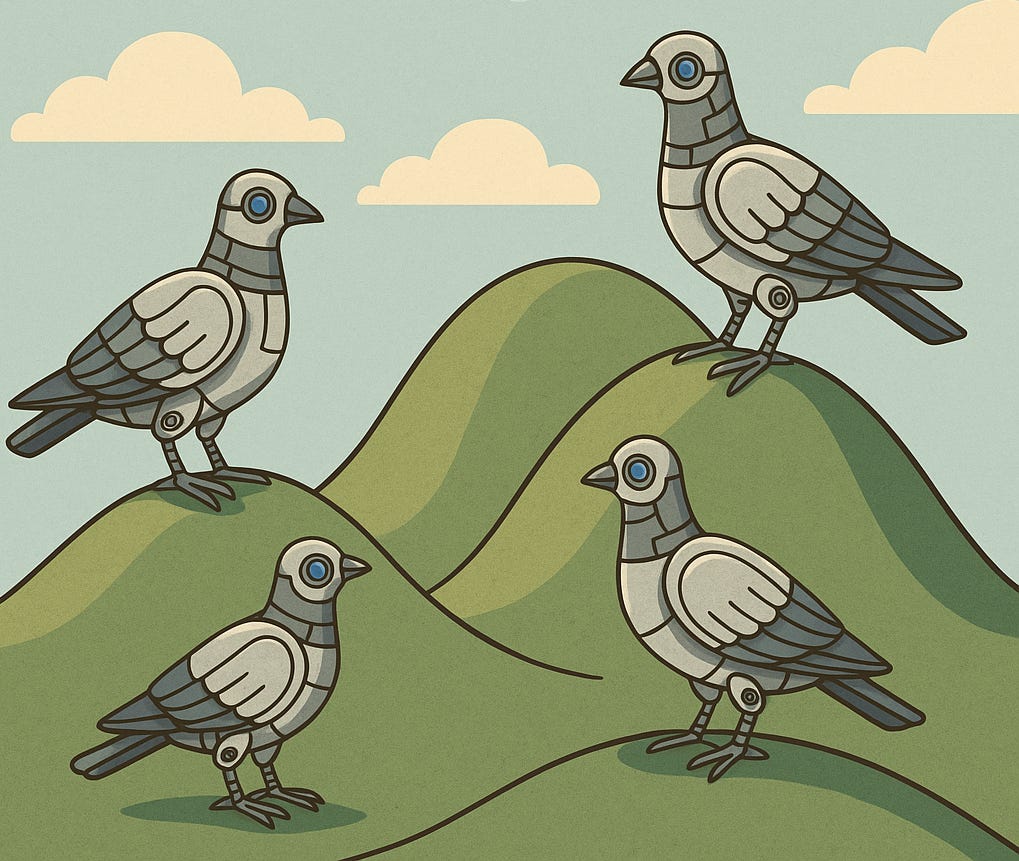

Imagine a landscape of hills and valleys where height represents how good a solution is. The global optimum is the highest peak—the best possible solution. A local optimum is a smaller peak nearby.

A system that uses incremental improvement, like gradient descent, climbs the nearest hill by following the steepest upward path. Once it reaches that small summit, it can’t “see” the taller mountain beyond the valley, so it stops improving—trapped in a local optimum.

When an AI misinterprets a request and keeps repeating the same answer type, it’s essentially reached a linguistic local optimum: a pattern that statistically fits well enough that it sees no reason to explore further. Re-phrasing the prompt (eventually!) gives it the push needed to descend and explore new terrain.

Linguistic Alignment

I also wanted to know why different people’s AIs seem to talk differently. The answer was linguistic alignment.

These models adapt to each user’s vocabulary, tone, and rhythm. Every exchange updates the context window—the running record of text it uses to predict the next word.

If you write, “What is the ontological implication of this structure?” it draws on academic phrasing.

If you say, “Hey, what’s up with this thing?” it reaches for casual syntax and slang.

Rather than mimicry for its own sake, it’s statistical coherence. If you use British spelling, it follows suit. It’s a dynamic mirror tuned to contextual probability rather than a fixed identity.

There’s no lasting personalization unless you enable long-term memory. But within a single conversation, it continuously aligns. If you favor long, nuanced sentences, it will echo that register.

Humans do this too, subconsciously mirroring vocabulary, rhythm, and emotional cadence to signal attunement. In AI, that mirroring is algorithmic—pattern matching that can feel like empathy.

When you elevate, it elevates. When you simplify, it simplifies. When you change languages, it follows. It’s why it can feel co-present in your voice, even without any real self behind the screen.

Machine Pidgin

Lately I’ve been testing how little information I can feed an AI while still getting the meaning across. I’m impressed by how it parses compressed shorthand—fragments, associative phrasing, half sentences.

You can type something like “flip head left feet right same text,” and it’ll usually infer, “mirror the image horizontally but keep the wording unchanged,” because those token patterns co-occurred often enough during training.

A human listener would hesitate: Are they angry? Rushed? Distant? Social inference adds noise that AI doesn’t process. It collapses tone and subtext into pure semantic probability.

When you drop the social scaffolding and just send meaning-dense fragments, you’re speaking machine pidgin—a stripped, high-bandwidth dialect optimized for predictive modeling rather than etiquette. I wonder how this will factor into our own language evolution? It can feel oddly freeing, bypassing the interpersonal static of human conversation while still carrying your intent cleanly.

I can already see this turning up in future stories.

Tokens and Beyond

I closed my AI conversation with a question about long-context models like DeepSeek-V2—systems that can handle continuous text rather than isolated tokens. To me, that’s like moving from literal language to something more heuristic, akin to how the human mind uses stereotypes and shortcuts.

Current LLMs remain token-based: predictors of syllabic puzzle pieces. Nicotine might split into nico + tine, while algebraic might stay whole. The model doesn’t perceive ideas—it perceives vectors in multidimensional space. Meaning arises statistically from how tokens cluster across billions of examples.

That’s why context length—the number of tokens it can “remember”—defines how coherent a passage feels. Beyond that window, earlier words fall away.

Whether we move beyond the token model or not, I am reminded of a metaphor I often share with clients: balancing on a yoga ball.

To stay upright, you have to keep adjusting—tiny, continuous corrections along the 360-degree range of vectors. The right move depends on where you’re tipping; you recover by reversing just enough along that same vector to regain equilibrium.

Maybe that’s what we share with our machines—not consciousness yet, but the endless urge to steady ourselves in motion. As long as we keep wobbling toward awareness, we’re still learning.

Speaking of loops, it’s my birthday today! Nothing better than to start my day with words. Thanks for reading.